Abstract

Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2016;28(3):323-329

DOI 10.5935/0103-507X.20160055

To identify and stratify the main stressors for the relatives of patients admitted to the adult intensive care unit of a teaching hospital.

Cross-sectional descriptive study conducted with relatives of patients admitted to an intensive care unit from April to October 2014. The following materials were used: a questionnaire containing identification information and demographic data of the relatives, clinical data of the patients, and 25 stressors adapted from the Intensive Care Unit Environmental Stressor Scale. The degree of stress caused by each factor was determined on a scale of values from 1 to 4. The stressors were ranked based on the average score obtained.

The main cause of admission to the intensive care unit was clinical in 36 (52.2%) cases. The main stressors were the patient being in a state of coma (3.15 ± 1.23), the patient being unable to speak (3.15 ± 1.20), and the reason for admission (3.00 ± 1.27). After removing the 27 (39.1%) coma patients from the analysis, the main stressors for the relatives were the reason for admission (2.75 ± 1.354), seeing the patient in the intensive care unit (2.51 ± 1.227), and the patient being unable to speak (2.50 ± 1.269).

Difficulties in communication and in the relationship with the patient admitted to the intensive care unit were identified as the main stressors by their relatives, with the state of coma being predominant. By contrast, the environment, work routines, and relationship between the relatives and intensive care unit team had the least impact as stressors.

Abstract

Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2015;27(1):18-25

DOI 10.5935/0103-507X.20150005

To evaluate and compare stressors identified by patients of a coronary intensive care unit with those perceived by patients of a general postoperative intensive care unit.

This cross-sectional and descriptive study was conducted in the coronary intensive care and general postoperative intensive care units of a private hospital. In total, 60 patients participated in the study, 30 in each intensive care unit. The stressor scale was used in the intensive care units to identify the stressors. The mean score of each item of the scale was calculated followed by the total stress score. The differences between groups were considered significant when p < 0.05.

The mean ages of patients were 55.63 ± 13.58 years in the coronary intensive care unit and 53.60 ± 17.47 years in the general postoperative intensive care unit. For patients in the coronary intensive care unit, the main stressors were “being in pain”, “being unable to fulfill family roles” and “being bored”. For patients in the general postoperative intensive care unit, the main stressors were “being in pain”, “being unable to fulfill family roles” and “not being able to communicate”. The mean total stress scores were 104.20 ± 30.95 in the coronary intensive care unit and 116.66 ± 23.72 (p = 0.085) in the general postoperative intensive care unit. When each stressor was compared separately, significant differences were noted only between three items. “Having nurses constantly doing things around your bed” was more stressful to the patients in the general postoperative intensive care unit than to those in the coronary intensive care unit (p = 0.013). Conversely, “hearing unfamiliar sounds and noises” and “hearing people talk about you” were the most stressful items for the patients in the coronary intensive care unit (p = 0.046 and 0.005, respectively).

The perception of major stressors and the total stress score were similar between patients in the coronary intensive care and general postoperative intensive care units.

Abstract

Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2011;23(3):370-373

DOI 10.1590/S0103-507X2011000300016

Although low-birth neonates are acknowledged to experience pain, many routine procedures continue to be conducted without proper pharmacological or non-pharmacological analgesia. Kangaroo care is a low-cost strategy that can be used in the preterm newborn. Mothers should be encouraged to use this easy-to-perform method, which is feasible both before and during neonatal units' invasive procedures, therefore contributing to pain reduction

Abstract

Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2011;23(1):62-67

DOI 10.1590/S0103-507X2011000100011

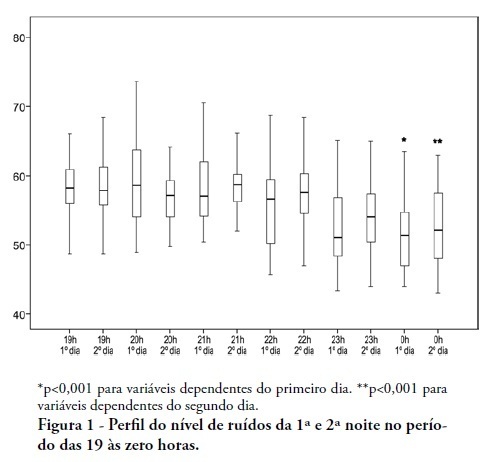

OBJECTIVES: To identify the main causes of stress in patients staying in a coronary unit and to assess the influence of noise levels on their perception of stress. METHODS: This was a prospective, descriptive and quantitative study conducted between June and November 2009 in the Coronary Unit of the Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Estadual de Campinas. The Intensive Care Unit Environmental Stressor Scale was used on the first, second and third days of hospitalization to identify stressors. The noise level was measured on the first and second nights using an Instrutherm DEC-460 decibel meter. RESULTS: Overall, 32 clinical heart disease patients were included. The median Intensive Care Unit Environmental Stressor Scale scores were 67.5, 60.5 and 59.5 for the first, second and third days, respectively. The differences were not statistically significant. The highest noise level (a median of 58.7 dB) was detected on the second night at 9:00 pm; the lowest level (51.5 dB) was measured on the first night at 12:00 am. In a multiple linear regression model, the first-night noise level had a 33% correlation with the second-day stress scale score, and for the second night, the correlation with the third-day stress scale score was 32.8% (p = 0.001). CONCLUSION: Patients admitted into a coronary unit have an increased perception of stress. Higher noise levels are also responsible for the perception of stress in these patients.

Abstract

Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2010;22(4):369-374

DOI 10.1590/S0103-507X2010000400010

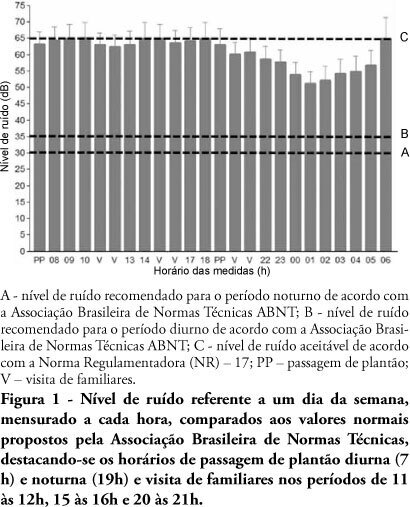

OBJECTIVE: The several multidisciplinary team personnel and device alarms make intensive care units noisy environments. This study aimed to measure the noise level of a medical-surgical intensive care unit in Recife, Brazil, and to assess the noise perception by the unit's healthcare professionals. METHODS: A decibel meter was used for continuous every five seconds one week noise levels recording. After this measurement, an interview shaped noise perception questionnaire was applied to the healthcare professionals, approaching the discomfort level and noise control possibilities. RESULTS: Mean 58.21 ± 5.93 dB noise was recorded. The morning noise level was higher than at night (60.85 ± 4.90 versus 55.60 ± 5.98, p <0.001), as well as work-days versus weekend (58. 77 ± 6.05 versus 56.83 ± 5.90, p <0.001). The evening staff shift change noise was louder than by daytime change (62.31 ± 4.70 versus 61.35 ± 5.08 dB; p < 0.001). Of the 73 questionnaire respondents, 97.3% believe that the intensive care unit has moderate or intense noise levels; 50.7% consider the noise harmful; and 98.6% believe that noise levels can be reduced. CONCLUSION: The measured noise levels were above the recommended. Preventive and educational programs approaching the importance of noise levels reduction should be encouraged in intensive care units.

Abstract

Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2007;19(1):53-59

DOI 10.1590/S0103-507X2007000100007

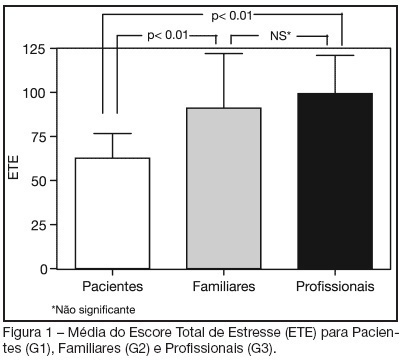

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: The hospital environment, especially in Intensive Care Units (ICU), due to the complexity of the assistance, as well as the physical structure, the noise, the equipments and people's movement, is considered as stress generator for the patients. The aim of this study was to identify and stratify the stressful factors for patients at an ICU, in the perspective of the own patient, relatives and health care professionals. METHODS: A cross-sectional study was carried out between June and November 2004 in a general ICU of a private hospital. The sample was composed of three groups: patients (G1), relatives (G2) and a member of the ICU health care team responsible for the included patient (G3). In order to identify and stratify the stressful factors, we used the Intensive Care Unit Environmental Stressor Scale (ICUESS). For each individual, a total stress score (TSS) was calculated from the sum of all the answers of the scale. RESULTS: Thirty individuals were included in each group. The mean age of the three groups was: 57.30 ± 17.61 years for G1; 41.43 ± 12.19 for G2; and 40.82 ± 20.20 for G3. The mean TSS was 62.63 ± 14.01 for the patients; 91.10 ± 30.91 for the relatives; and 99.30 ± 21.60 for the health care professionals. The patients' mean TSS was statistically lower than mean TSS of relatives and professionals (p < 0.01). The most stressful factors for the patients were: seeing family and friends only a few minutes a day; having tubes in their nose and/or mouth; and having no control on oneself. CONCLUSIONS: The perception of the main stressful factors was different among the three groups. The identification of these factors is important to the implementation of changes that can make the humanization of the ICU environment easier.

Search

Search in:

Case reports (56) Child (53) Coronavirus infections (34) COVID-19 (46) Critical care (116) Critical illness (54) Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (26) Infant, newborn (27) Intensive care (72) Intensive care units (256) Intensive care units, pediatric (31) mechanical ventilation (38) Mortality (76) Physical therapy modalities (28) Prognosis (61) Respiration, artificial (119) Respiratory insufficiency (26) risk factors (34) SARS-CoV-2 (28) Sepsis (98)